Law for Sustainability, Sustainability Policy and Events

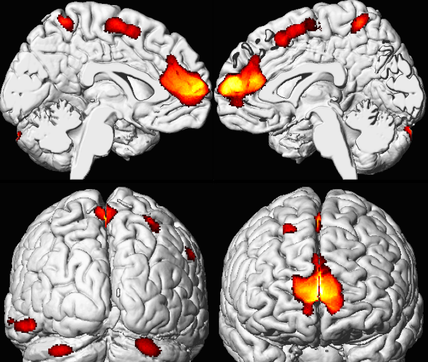

From “Decreased Brain Volume in Adults with Childhood Lead Exposure”, Cecil, Brubaker, et al., PLoS Med. 2008 May; 5(5): e112

Even if no one cares, I feel bad that I have posted only one blog at this site in 2021. I suppose I have been like so many who took the election of Joe Biden as a reason to take a break from what feels like the front lines of a very tiring war. Constantly attending to environmental issues, and the battle for the rule of law, for reason and mutual respect, can be like carrying a heavy weight. Environmental citizens need rest sometimes from carrying that weight. But picking it up again can make you feel strong, purposeful, engaged. And despite the continuing darkness of the news, there are signs of light – there is a real prospect now of money flowing to much-needed efforts, such as the removal of lead from our homes and surroundings.

In my class Research for Environmental Agencies and Organizations I offer students a list of projects, and each semester I include something about lead poisoning prevention. One student signed on to help me promote a bill that is now before the Massachusetts legislature[1], submitted by Senator Patricia Jehlen, similar to a bill she submitted many years ago. The intent of the bill is to overcome the barriers to suing those who recklessly placed lead in commerce, knowing it will harm people, and doing nothing to prevent that harm. If companies make a product that they ought to know would likely harm people, the law should provide for both compensation to victims and punishment for those who unreasonably cause harm, so that others will be deterred from doing the same thing. But when you can’t prove that the harm you experienced was caused by a particular company that company gets away with their malfeasance. The bill that Jehlen put forth many years ago would have imposed “market share liability”, allowing the apportionment of liability according to the market share a company had of that product, treating all the members of industry who behaved the same way as culpable. The current bill allows the court more flexibility to determine how to allocate responsibility, but it’s the same idea: no one should get away with such anti-social behavior simply because the specific product maker can’t be identified.

In my class Research for Environmental Agencies and Organizations I offer students a list of projects, and each semester I include something about lead poisoning prevention. One student signed on to help me promote a bill that is now before the Massachusetts legislature[1], submitted by Senator Patricia Jehlen, similar to a bill she submitted many years ago. The intent of the bill is to overcome the barriers to suing those who recklessly placed lead in commerce, knowing it will harm people, and doing nothing to prevent that harm. If companies make a product that they ought to know would likely harm people, the law should provide for both compensation to victims and punishment for those who unreasonably cause harm, so that others will be deterred from doing the same thing. But when you can’t prove that the harm you experienced was caused by a particular company that company gets away with their malfeasance. The bill that Jehlen put forth many years ago would have imposed “market share liability”, allowing the apportionment of liability according to the market share a company had of that product, treating all the members of industry who behaved the same way as culpable. The current bill allows the court more flexibility to determine how to allocate responsibility, but it’s the same idea: no one should get away with such anti-social behavior simply because the specific product maker can’t be identified.

The legal scholar Lisa Heinzerling once wrote an article entitled “The Rights of Statistical People”,[2] making the point that regulatory policies that accept inevitable injury to some are different from allowing murder in that we can’t identify the victims in advance. In her conclusion she wrote:

“Describing pain and loss in statistical terms allows us to think coolly about them; it strips life-threatening risks of the moral and emotional texture they derive from their association with real humans with real bodies and real loved ones.”

To continue to accept our current legal structure, which does not include sufficiently effective compensation or deterrence, is a similar example of cold thinking (or absence of feeling). It ignores that the victims are real people with real families and ruined futures.

If the bill passes, there will not likely be a flood of litigation. Plaintiffs will not be able to sue just anyone, and will still have a steep climb to prove their case. But they will have a chance to do so, and without it, they really have no chance unless they are spectacularly lucky to have the evidence they need under the current law.

Legislative hearings on the bill attracted little attention (although a lobbyist showed up to oppose it[3]), so my student (Peri Taubman) and I have organized a conference entitled “Eliminating Lead Poisoning in 2022” which will take place December 9 (12:30 – 4 - see registration link below). It is clear that if we invested properly we could achieve this goal, and not only would it not break the bank, but it would be an intelligent investment in that most important resource of all, people.[4] When lead gets into the body, it can lodge in the brain, where it stops the functioning of that organ at that spot. Many people are aware that lead poisoning causes reductions in IQ. But it also interferes with our ability to make executive decisions, to control our impulses. It is associated with increases in crime, violence, dropping out of school. The research on this shows the same thing repeatedly: lead degrades us. Putting it simply: what kind of people do we want to be? What is economically intelligent about failing to act to prevent this result? Not to mention the cost of the impacts on health, and not to mention that we know more about its impacts on adults now, including cardiovascular health. Do we want to damage children and die earlier than we should?

Environmental citizens can argue about what are the worst problems out there, and climate change is going to be nominated as number one, or extinctions, or overpopulation, or toxins and plastic everywhere. But there’s a good case that lead should be at the top of the list, not just because it is so harmful (and especially to children, society’s future), but because its harm is unnecessary, and we should have acted long ago. Even though we have acted since, we have not done so sufficiently, and that is a cause for shame. We should be proud of what we have done – and our actions (such as banning it in gasoline and residential paint) have made a huge difference – poisonings have dramatically declined. But the problem remains. You can look at our record and ask why have we stopped the effort? It’s as if we were drowning and swam towards shore, but then stopped before we got there. We’re still in the water, though the goal is within sight. Until we remove lead from our lives, it will continue to cause unnecessary misery. It is a persistent poison – once extracted from the underworld where it should have remained, it does not break down but claims new victims continuously. We have to be persistent in response to this threat. Yes, it has important uses – but only those that can contain it should be permitted. This is a technical problem we can solve if we have the sociopolitical will to do so.

If you are not doing anything December 9th (from 12:30 to 4:30) please consider joining us as we hear from a series of experts. We’ll hear about how Philadelphia has instituted requirements that rentals must be lead-safe, how Boston has a roadmap for eliminating lead poisoning, how New York City has acted on lead in items like spices and amulets. We’ll hear from leading experts on lead in wildlife, soil, and shooting, topics not always included in discussions that give you the impression the problem is only about paint or water. (Just pause for a moment to consider the connection between the impact on our capacity to make good judgment and guns). We’ll hear from leaders like David Jacobs, Chief Scientist at the National Center for Healthy Housing, and Philip Landrigan, whose pioneering work on lead helped convince Congress to act. We’ll talk about bills before the legislature and what we should do nationally, and how we can use the money that will come flowing down to the states, to eliminate this avoidable scourge, and at long last wipe this shame from the face of our civilization.

It’s free. To register, go to: https://bostonu.zoom.us/meeting/register/tJYlfuygrTwoGtecmkeGQzTuFf1mIS_RA0_l.[5]

[1] An Act Enhancing Justice for Families Harmed by Lead, S. 1056, https://malegislature.gov/Bills/192/S1056. Representative David Laboeuf has submitted the same bill in the House. I thank Rick Rabin, Eugene Benson, Erik Olson, Laura Maslow-Armand and Neil Leifer for help in drafting the bill.

[2] 24 Harv. Envtl. L. Rev. 189-207 (2000), https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/327/

[3] Because of the questioning of Senator Jamie Eldridge, we learned that he was paid by the lead industry.

[4] Studies consistently find that lead poisoning exacts a huge monetary cost (as well as personal tragedy) on society, and quite often that benefits exceed the costs of program implementation. For example, the Health Impact Project of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Pew Charitable Trusts found that “Removing leaded drinking water service lines from the homes of children born in 2018 would protect more than 350,000 children and yield $2.7 billion in future benefits, or about $1.33 per dollar invested”, and “Eradicating lead paint hazards from older homes of children from low-income families would provide $3.5 billion in future benefits, or approximately $1.39 per dollar invested, and protect more than 311,000 children.”

https://altarum.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-publication-files/HIP_Childhood_Lead_Poisoning_report.pdf

[5] If you are in Boston and want to come in person, email [email protected]. For a full copy of the agenda or questions about this event, write me at [email protected].

“Describing pain and loss in statistical terms allows us to think coolly about them; it strips life-threatening risks of the moral and emotional texture they derive from their association with real humans with real bodies and real loved ones.”

To continue to accept our current legal structure, which does not include sufficiently effective compensation or deterrence, is a similar example of cold thinking (or absence of feeling). It ignores that the victims are real people with real families and ruined futures.

If the bill passes, there will not likely be a flood of litigation. Plaintiffs will not be able to sue just anyone, and will still have a steep climb to prove their case. But they will have a chance to do so, and without it, they really have no chance unless they are spectacularly lucky to have the evidence they need under the current law.

Legislative hearings on the bill attracted little attention (although a lobbyist showed up to oppose it[3]), so my student (Peri Taubman) and I have organized a conference entitled “Eliminating Lead Poisoning in 2022” which will take place December 9 (12:30 – 4 - see registration link below). It is clear that if we invested properly we could achieve this goal, and not only would it not break the bank, but it would be an intelligent investment in that most important resource of all, people.[4] When lead gets into the body, it can lodge in the brain, where it stops the functioning of that organ at that spot. Many people are aware that lead poisoning causes reductions in IQ. But it also interferes with our ability to make executive decisions, to control our impulses. It is associated with increases in crime, violence, dropping out of school. The research on this shows the same thing repeatedly: lead degrades us. Putting it simply: what kind of people do we want to be? What is economically intelligent about failing to act to prevent this result? Not to mention the cost of the impacts on health, and not to mention that we know more about its impacts on adults now, including cardiovascular health. Do we want to damage children and die earlier than we should?

Environmental citizens can argue about what are the worst problems out there, and climate change is going to be nominated as number one, or extinctions, or overpopulation, or toxins and plastic everywhere. But there’s a good case that lead should be at the top of the list, not just because it is so harmful (and especially to children, society’s future), but because its harm is unnecessary, and we should have acted long ago. Even though we have acted since, we have not done so sufficiently, and that is a cause for shame. We should be proud of what we have done – and our actions (such as banning it in gasoline and residential paint) have made a huge difference – poisonings have dramatically declined. But the problem remains. You can look at our record and ask why have we stopped the effort? It’s as if we were drowning and swam towards shore, but then stopped before we got there. We’re still in the water, though the goal is within sight. Until we remove lead from our lives, it will continue to cause unnecessary misery. It is a persistent poison – once extracted from the underworld where it should have remained, it does not break down but claims new victims continuously. We have to be persistent in response to this threat. Yes, it has important uses – but only those that can contain it should be permitted. This is a technical problem we can solve if we have the sociopolitical will to do so.

If you are not doing anything December 9th (from 12:30 to 4:30) please consider joining us as we hear from a series of experts. We’ll hear about how Philadelphia has instituted requirements that rentals must be lead-safe, how Boston has a roadmap for eliminating lead poisoning, how New York City has acted on lead in items like spices and amulets. We’ll hear from leading experts on lead in wildlife, soil, and shooting, topics not always included in discussions that give you the impression the problem is only about paint or water. (Just pause for a moment to consider the connection between the impact on our capacity to make good judgment and guns). We’ll hear from leaders like David Jacobs, Chief Scientist at the National Center for Healthy Housing, and Philip Landrigan, whose pioneering work on lead helped convince Congress to act. We’ll talk about bills before the legislature and what we should do nationally, and how we can use the money that will come flowing down to the states, to eliminate this avoidable scourge, and at long last wipe this shame from the face of our civilization.

It’s free. To register, go to: https://bostonu.zoom.us/meeting/register/tJYlfuygrTwoGtecmkeGQzTuFf1mIS_RA0_l.[5]

[1] An Act Enhancing Justice for Families Harmed by Lead, S. 1056, https://malegislature.gov/Bills/192/S1056. Representative David Laboeuf has submitted the same bill in the House. I thank Rick Rabin, Eugene Benson, Erik Olson, Laura Maslow-Armand and Neil Leifer for help in drafting the bill.

[2] 24 Harv. Envtl. L. Rev. 189-207 (2000), https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/327/

[3] Because of the questioning of Senator Jamie Eldridge, we learned that he was paid by the lead industry.

[4] Studies consistently find that lead poisoning exacts a huge monetary cost (as well as personal tragedy) on society, and quite often that benefits exceed the costs of program implementation. For example, the Health Impact Project of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Pew Charitable Trusts found that “Removing leaded drinking water service lines from the homes of children born in 2018 would protect more than 350,000 children and yield $2.7 billion in future benefits, or about $1.33 per dollar invested”, and “Eradicating lead paint hazards from older homes of children from low-income families would provide $3.5 billion in future benefits, or approximately $1.39 per dollar invested, and protect more than 311,000 children.”

https://altarum.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-publication-files/HIP_Childhood_Lead_Poisoning_report.pdf

[5] If you are in Boston and want to come in person, email [email protected]. For a full copy of the agenda or questions about this event, write me at [email protected].

RSS Feed

RSS Feed