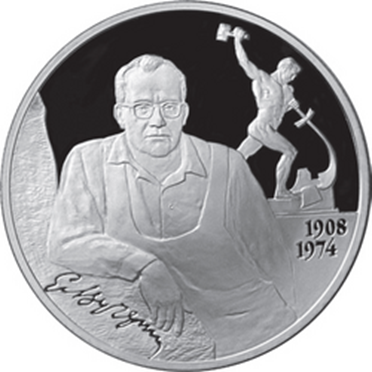

Yevgeny Vuchetich, sculptor of the 1959 gift to the UN from the Soviet Union of a bronze statue “promoting the slogan Let Us Beat Swords Into Plowshares”. (Wikipedia). A rare instance of that organization quoting the Bible. (Isaiah 2:4).

Environmental citizens have a lot to think about. Being an environmentalist means allowing what’s happening in the environment around you to become part of your internal world. As Katha Pollitt and others have said, all politics is personal. Each of us makes a personal decision about what we can focus on. The issues we don’t choose to think about often remain unresolved.

Amongst all the problems we have, the nuclear threat continues to loom unnecessarily large, destabilizing our sense of who we are and what we can be. It festers at the periphery of consciousness, poisoning our hopes for the future and making humanity’s aspirations seem ridiculous. Normally, we don’t have the time to focus on it. But the movie Oppenheimer provides an opportunity, as attention is drawn, to move our thinking to a more constructive place.

In 1962, Herman Kahn wrote Thinking About the Unthinkable, about his work as a pioneer in the field of nuclear military strategy. The concept of unthinkability was meant to refer to the horror of nuclear war. But it can also represent the idea that nuclear policy has been a matter reserved for certain experts, not the general public. It implies we ordinary members of the human race, though all affected personally by this matter, cannot be trusted to think about it correctly. To replace it we ask military specialists and game theorists to take over. This was not something the public ever chose, but something we find ourselves having inherited.

Amongst all the problems we have, the nuclear threat continues to loom unnecessarily large, destabilizing our sense of who we are and what we can be. It festers at the periphery of consciousness, poisoning our hopes for the future and making humanity’s aspirations seem ridiculous. Normally, we don’t have the time to focus on it. But the movie Oppenheimer provides an opportunity, as attention is drawn, to move our thinking to a more constructive place.

In 1962, Herman Kahn wrote Thinking About the Unthinkable, about his work as a pioneer in the field of nuclear military strategy. The concept of unthinkability was meant to refer to the horror of nuclear war. But it can also represent the idea that nuclear policy has been a matter reserved for certain experts, not the general public. It implies we ordinary members of the human race, though all affected personally by this matter, cannot be trusted to think about it correctly. To replace it we ask military specialists and game theorists to take over. This was not something the public ever chose, but something we find ourselves having inherited.

The movie will raise attention to a critical moment in history, when the man who led the bomb development effort was deprived of his clearance to be part of further deliberation. This was a personal insult to him, but it hurt us all.[i] He had an approach to nuclear that may have been the best we could have had at the time, when there were former atomic scientists agitating for an international body to control the weaponry on one side, military thinkers seeing only more power on the other (and suppressing news about what the scientists thought), and everyone scared to death. Oppenheimer took the view that a small atomic arsenal was sufficient, and we should not escalate into an arms race or build a hydrogen bomb.[ii] Removing him replaced reason with power based on Old World thinking. The idea that modern math-enabled thinkers can be trusted to keep us safe has served to distract us from the fact that our nuclear policy is a simple application of the old us v. them framework. That’s so thinkable it’s immediately apparent we need to be rethinking things once you do it.

That military perspective is necessary for defense against attacks. But someone who raises a shield all the time never meets his neighbor, and someone who points his weapons at others causes them to raise their shields. The conduct of foreign policy with the military perspective alone is bankrupt of the possibility of making peace, unless it is a military with the capacity to understand peacemaking, and its role in creating the safe space for democracy to take place. Because nuclear weapons represent a destructiveness that threatens everyone, it is a matter concerning which every human has the same stake in resolution. We all need the safe space to come together on this.

Though the problem has its roots in the personal (when you think of competing male mammals it feels like its roots are also in the instinctual), it has morphed into an impersonal force, an implacable logic. (See, for example, the 1983 movie War Games). Recasting the issue in terms of the personal – if universal – reverses that hardening. The complex strategic positioning drawn from the logic of hostile relationships cannot transform others into friends, but learning to be a friend is how a nation contributes to the survivability of our world.

The Doomsday Machine of the 1964 movie Dr. Strangelove has taken on bloodless form with complex systems now in place for the delivery of nuclear devastation, and we are threatened not just with the possibility of an amoral leader like Putin pressing the button but with mistake, as the movie 1964 movie Fail Safe depicted and as has happened. We’ve been saved by people like Russian officer Stanislav Petrov, who refused to launch missiles, taking the chance that the alerts telling him the US was attacking Russia were false.[iii] During the Cuban Missile crisis when we were dropping depth charges on a nuclear-armed sub to get it to surface, Soviet officer Vasili Arkhipov kept his cool.[iv]

These real people who prevented the destruction the nuclear machine would have brought should be culturally important. The system does not think as people do so we need to insert ourselves. People built this problem into our environment, and people can take it out. When the issue is understood not in technical terms but as a failure of personhood, the failure to be human, there is the possibility for motivation to arise for a more fully human course of action. This seems to me to be or to represent a chance that we can learn to more realistically protect life. Thinkability can lead to learning.

I’ve tried to think about these things ever since being a little annoyed by the term “Unthinkable” when I first heard it at the age of ten. I saw the clear moral imperative then, and it seemed to me that everyone else I knew did, too. I was briefly paid, in my thirties, (a tiny amount), to produce a newsletter called Radiation Events Monitor, (for a group called the Center for Atomic Radiation Studies, led by Dr. Donnell Boardman). I worked pro-bono with another lawyer, (Dan Burnstein), to help widows of “atomic veterans” seek compensation for their husband’s deaths from the Veterans Administration.[v] I went to conferences and met people touched by the tragedies of nuclear uses. The issues are complex, but some things become very clear when you turn your attention to them: many poisonings were truly unnecessary and the attitude that created and accepted them must be seen as heartless, mindless, or both. I don’t know enough to say anyone in particular is a principal villain here. I don’t even see this as caused by villainy at all, but rather by an absence, a lack of morality in the system, a hole, a wound, a cutting distance from the source forces of living intelligence.

Many take up the issue of the bombing of Hiroshima. There are arguments in favor of it. You may not like them, you may not want to like them, but they exist, and it is hard to imagine what it would have been like to be Harry Truman. But consider the argument for the bombing of Nagasaki.

The United States can and ought to show that it has the courage to look at itself and recognize the wrongfulness here even if we do not understand the reasons for it. Failure to acknowledge this original sin displays an inability to self-reflect which can feel like sociopathic behavior to others in the community of nations. It is a key turning point that we must understand. It seems to reflect the logic of momentum, the logic of overwhelming force. However we grasp at it we see there is something human missing at the very beginning. It is still missing.[vi]

Thinking that nuclear weapons could be a tool of diplomacy – that threatening their use would cause other countries to pay attention to our priorities – demonstrated a lack of historical understanding. Among the figures who launched “atomic diplomacy” was Truman’s Secretary of State James Byrne. The Atomic Heritage Museum puts it this way: he thought the bomb “might put us in a position to dictate our own terms at the end of the war.”[vii] By the age-old logic of military thinking, this seems clear, that the bomb is power, and what you want is to be dictating your own terms.

But history shows that people often get their back up when dictated to. Threatening to kill them can increase their resistance. The bombing of England stiffened resolve against Hitler, as Putin’s attack on the Ukraine has created a national movement to fight back, as our efforts in VietNam inspired the VietCong, to cite just a few examples. The idea that threatening to nuke a people will make them compliant is crude, childish, incorrect. Our nuclear threat today gives credence to the leader of the cruel North Korean state, and to the Supreme Leader of Iran, not to mention China. We can do better by thinking about nations the way we think about people, deserving of respect and willing to fight for their dignity. The nuclear option does not fit the real model of interpersonal relationships. It blows it up by its very existence.

Nuclear war is a personal issue for every citizen of the world because all life can be poisoned and billions killed. If we care about the safety of anything we have a responsibility to do what we can about this. It is a very frightening thing to think about, yes, but not unthinkable. If we can sit with the issue the chances of what we do regard as unthinkable happening will be reduced. It is primarily a socio-psychological matter, not one that the military can solve. As the back cover of Joel Kovel’s 1984 Against the State of Nuclear Terror puts it:

There are, says Kovel, two kinds of nuclear states. There is the nuclear state apparatus whose ruling principle is domination through science; and there is the nuclear "state of being" which includes the psychology of living under the nuclear gun. The nuclear crisis is not a matter (of) technically adjusting the nature and number of warheads, but the agony and paranoia of an entire civilization.”

It is not fun to think about what happened to people in Hiroshima, or how history will regard our creation and use of the threat, or the potential long-term world poisoning by fallout, nuclear winter, the generation of horrific wastes, the cancers caused. It seems easier not to select it as something to spend time on, and to leave it to others to think about. But that’s part of the story about why we remain in this hellish mess.

This movie will bring needed attention to the personal tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, a man who was humiliated after giving unstinting service to this country, considered a “crybaby” by Truman and smeared as possibly disloyal and/or untrustworthy. But his tragedy is a personal window into a much larger story about an impersonal force: the response to terror with the irrational concept that a greater terror will bring about safety. This logic created the arms race that now holds a knife to the throat of life on Earth. The challenge now is to use this moment to achieve some clarity about how we can move to reduce the threat of nuclear armaments.

If we get over the reluctance to think about it, we can actually see what does and does not make sense. The system of Mutual Assured Destruction and Nixon’s Madman Theory (if the other side believes you are crazy enough to push the button, they will give in) can no longer be regarded as sensible when we see how Putin is using it to prevent the US from arming Ukraine with the tools for a more responsive offense. The failure to disarm the nuclear system works to the advantage of the Madman, not us, or anyone. Nixon was wrong to use the theory.

Consider the binary deterrence system we are locked into with Russia. It makes little sense when other countries have gained nuclear weapons. History also shows the system can destroy the world by mistake. Recognizing the absurdity of inadvertently ending civilization should bring us up short and motivate rethinking.

Albert Einstein gave this matter a lot of thought and repeatedly said we needed supranational control. (We do have an international atomic energy body but it doesn’t control what’s going on). I am hoping that this movie will prompt more people to look back at what that smart man said, as, for example, in The Atlantic, in “Atomic War or Peace”, November, 1947:

…in blaming the Russians the Americans should not ignore the fact that they themselves have not voluntarily renounced the use of the bomb as an ordinary weapon in the time before the achievement of supranational control, or if supranational control is not achieved. Thus they have fed the fear of other countries that they consider the bomb a legitimate part of their arsenal so long as other countries decline to accept their terms for supranational control.

Americans may be convinced of their determination not to launch an aggressive or preventive war. So they may believe it is superfluous to announce publicly that they will not a second time be the first to use the atomic bomb. But this country has been solemnly invited to renounce the use of the bomb—that is, to outlaw it—and has declined to do so unless its terms for supranational control are accepted.

Thinking about nuclear issues can reduce the distress we feel, because thinking can lead to solutions, whereas ignoring the issue most certainly does not. If the movie leads to more people informing themselves, perhaps we can move from the primitive cultural reception of the nuclear age that named a sexy bathing suit after the island where the first demonstration blast was held, and gave us comic book heroes who gained superpowers by being irradiated.

Einstein drew attention, as he would do, to the fundamental laws in operation. His theory here of moral gravity seems proven by history:

It should not be forgotten that the atomic bomb was made in this country as a preventive measure; it was to head off its use by the Germans, if they discovered it…But now, without any provocation, and without the justification of reprisal or retaliation, a refusal to outlaw the use of the bomb save in reprisal is making a political purpose of its possession; this is hardly pardonable…

To keep a stockpile of atomic bombs without promising not to initiate its use is exploiting the possession of bombs for political ends. It may be that the United States hopes in this way to frighten the Soviet Union into accepting supranational control of atomic energy. But the creation of fear only heightens antagonism and increases the danger of war.

In 2020 Greg Mitchell, former editor of Nuclear Times, wrote in Newsweek:

Seventy-five years have now passed since the United States initiated a policy known as "first use" with its atomic attack on Hiroshima. Three days later, on August 9, 1945, it was affirmed with a second detonation over the city of Nagasaki. No nuclear attacks have followed since, although many Americans are probably unaware that this first-strike policy very much remains in effect.[viii]

No matter what we say about our first strike policy a military planner in another country would have to assume we might have one, and even if we were clear that we would not do that, the system of the second or only defensive strike still leads to a horrifying arsenal too easily triggered. A 2019 piece in Rethink Progress by Luisa Rodriguez reviews the current state of this expensive and dangerous standoff.

The degree to which a nuclear war between the US and Russia could escalate depends on how many of their nuclear weapons would survive a first strike.

Therefore, they maintain a secure second strike to maintain deterrence. She finds:

…between ~990 and ~1,500 of the US’s deployed nuclear warheads and between ~450 and~1,240 of Russia’s deployed nuclear warheads would survive a first strike. However, improvements in technology could substantially threaten the survivability of deployment systems that have been considered ‘inherently survivable’ for decades.[ix]

The whole system is only vaporously comprehensible and is inherently extremely unstable. Clearly, we must at least rapidly return to Oppenheimer’s sense of an appropriately sized defensive stockpile, and concentrate on bringing everyone together to create Einstein’s supranational body that can control these weapons. Clarity about what our goals should be, about the kind of country we want to be, that makes clear we are a people who want to live and want others to live, is thinkable if we try. The nuclear threat must be repudiated as a tool of foreign policy. Let us say, as people do love to say on both sides of our politics, that we are the strongest country in the world. But let us not say that we are the best until we have used our strength to bring everyone together to disarm the nuclear option for all the world’s sake.

Those who recommend this course of action will be marked for hostility on the theory that lowering your shield allows an enemy to slash you with their sword. But threatening to use nuclear weapons has not increased our power. We have preserved our power only because we have not used them in anger after World War II. But we have lost the opportunity to rally the world behind us because we used them coercively, as a threat. (Though the issue is a bit confusing in that nuclear bombs are only valuable if not used, that does not make the matter unthinkable, only ironic). When former atomic scientist Joseph Rotblat accepted the 1995 Nobel Peace Prize that he shared with the Pugwash movement for nuclear disarmament, he noted that

There is no direct evidence that nuclear weapons prevented a world war. Conversely, it is known that they nearly caused one.[x]

Out of the recognition that something doesn’t make sense can come a more sensible way of seeing. In the matter of nuclear issues, many things get in the way of seeing what needs to be seen, but we become better people for being able to see things as they are. It is painful to think about what happened to the people in Japan - to read, for example, Keiji Nakazawa’s graphic novels, based on his own life experiences as a child of Hiroshima, in the series Barefoot Gen. We don’t flock to the theaters to see Akira Kurosawa’s 1955 I Live in Fear, about a father desperate to get his family out of Japan before the Americans would bomb it again. Why should an American read these extraordinarily sad stories and watch that movie? Because they are the opposite of impersonal. The human element brings clarity about what is needed.

Reading about nuclear strategy can be distressing – all those bombs and bomb-making factories that generate horrendous amounts of pollution and create horribly poisonous materials that will last thousands of years and cannot be safely disposed of.

We don’t seem to like to think about the Navajo uranium miners not provided with respiratory protection, the servicemen marched to ground zero in test blasts that only served to show you could injure hundreds of thousands of loyal Americans, the Japanese boat The Lucky Dragon, (Daigo Fukuryū Maru), doused with intense fallout from our hydrogen bomb tests, or how those fearsome events made the Marshall Islands so radioactive people have lost their homes, and nuclear waste remains piled up waiting for the rising sea to disperse it.

But we are able to think about these issues and to see how they all come together into one conclusion: We must use our power to create a safer world, while we can. We should never have used the nuclear genie to wish for dominance. Recognition of the harm this has caused is the first step. Now we must ask the genies of the other lamps of power for the granting of our wishes for peaceful relations, just and beautiful cultures, the building of trust and friendship, the sharing of the fate of life on this green earth.

Rotblat used the Nobel Prize award to remind us all of the manifesto Einstein produced in 1955 with Bertrand Russell and others:

We need to convey the message that safeguarding our common property, humankind, will require developing in each of us a new loyalty: a loyalty to mankind. It calls for the nurturing of a feeling of belonging to the human race. We have to become world citizens…All nations of the world have become close neighbors…In many ways we are becoming like one family…In advocating the new loyalty to mankind I am not suggesting that we give up national loyalties. Each of us has loyalties to several groups – from the smallest, the family, to the largest, at present, the nation. Many of these groups provide protection for their members. With the global threats resulting from science and technology, the whole of humankind now needs protection. We have to extend our loyalty to the whole of the human race.

What we are advocating in Pugwash, a war-free world, will be seen by many as a Utopian dream. It is not Utopian. There already exist in the world large regions, for example, the European Union, within which war is inconceivable. What is needed is to extend these to cover the world’s major powers.

In any case, we have no choice. The alternative is unacceptable. Let me quote the last passage of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto:

We appeal, as human beings, to human beings: Remember your humanity and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open for a new paradise; if you cannot, there lies before you the risk of universal death.

The movie Oppenheimer tells a personal story about a key figure. But we are all key figures in this story. When medical officer David Bradley wrote in 1948 about his experience trying to respond to the radioactive mess produced by the second blast at Bikini Atoll (an underwater bomb exposed many naval personnel to serious wet radioactivity), he titled his book No Place to Hide. We are all personally affected by the failure to grapple with and remove the nuclear threat from our lives. When enough stop trying to hide from it and begin to engage, when enough see how thinkable it really is, we might get ourselves off this road that only leads to Hell on Earth. No good reason impels us to travel this way, and brighter directions demand our attention. Before us now is the act of 92 nations signing and 68 active parties in the 2017 United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,[xi] nations that (or, perhaps better, who) among other things are

Deeply concerned about the catastrophic humanitarian consequences that would result from any use of nuclear weapons, and recognizing the consequent need to completely eliminate such weapons, which remains the only way to guarantee that nuclear weapons are never used again under any circumstances,

And are among other things

Determined to act with a view to achieving effective progress towards general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.

The future is in view and we can welcome and speed its arrival with the simple principles of friendly relationship applied to joint control that is “strict and effective”. Why not add the United States to the list of participants at https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVI-9&chapter=26&clang=_en? We might gain the strategic advantage of people not being afraid of us.

[i] See more at https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/16/science/j-robert-oppenheimer-energy-department.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/12/us/transcripts-kept-secret-for-60-years-bolster-defense-of-oppenheimers-loyalty.html

[ii] See, for example, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/coldwar/interviews/episode-8/york2.html or

“The Debate Over the Hydrogen Bomb”, Scientific American, Oct. 1, 1975, by Herbert York.

[iii] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-24280831

[iv] See Martin Sherwin’s 2020 Gambling with Armageddon.

[v] One of the husbands flew a plane that followed the radioactive cloud after bomb tests, and the pilot did not seem to have been given protective breathing equipment nor could we see that filters were used. We won one case but then it was overturned by HQ. When I later helped a former AF vet whose job involved long periods of time standing next to bombs (to reduce weight they have minimal shielding) I didn't mention his radiation exposure but submitted a claim based on his exposure to benzene. I had come to believe that the VA would not grant recognition of radiation injury because it would open the gates to a flood of claims from hundreds of thousands. We won full compensation.

[vi] The idea that momentum made the decision may be most appropriate, but that does not exclude factors like hubris or the doctrine of overwhelming force. For a great example of that at the very beginning of the colonial age see the story of how Magellan was killed, as told by William Manchester in his 1992 A World Lit Only By Fire. He seemed to think his display of new powers would frighten the enemy and that his righteousness would protect him.

[vii] https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/profile/james-f-byrnes/

[viii] https://www.newsweek.com/us-must-end-nuclear-first-strike-policy-opinion-1527038

[ix] https://rethinkpriorities.org/publications/would-us-and-russian-nuclear-forces-survive-a-first-strike

[x] https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1995/rotblat/lecture/

[xi] https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/2017/07/20170707%2003-42%20PM/Ch_XXVI_9.pdf

That military perspective is necessary for defense against attacks. But someone who raises a shield all the time never meets his neighbor, and someone who points his weapons at others causes them to raise their shields. The conduct of foreign policy with the military perspective alone is bankrupt of the possibility of making peace, unless it is a military with the capacity to understand peacemaking, and its role in creating the safe space for democracy to take place. Because nuclear weapons represent a destructiveness that threatens everyone, it is a matter concerning which every human has the same stake in resolution. We all need the safe space to come together on this.

Though the problem has its roots in the personal (when you think of competing male mammals it feels like its roots are also in the instinctual), it has morphed into an impersonal force, an implacable logic. (See, for example, the 1983 movie War Games). Recasting the issue in terms of the personal – if universal – reverses that hardening. The complex strategic positioning drawn from the logic of hostile relationships cannot transform others into friends, but learning to be a friend is how a nation contributes to the survivability of our world.

The Doomsday Machine of the 1964 movie Dr. Strangelove has taken on bloodless form with complex systems now in place for the delivery of nuclear devastation, and we are threatened not just with the possibility of an amoral leader like Putin pressing the button but with mistake, as the movie 1964 movie Fail Safe depicted and as has happened. We’ve been saved by people like Russian officer Stanislav Petrov, who refused to launch missiles, taking the chance that the alerts telling him the US was attacking Russia were false.[iii] During the Cuban Missile crisis when we were dropping depth charges on a nuclear-armed sub to get it to surface, Soviet officer Vasili Arkhipov kept his cool.[iv]

These real people who prevented the destruction the nuclear machine would have brought should be culturally important. The system does not think as people do so we need to insert ourselves. People built this problem into our environment, and people can take it out. When the issue is understood not in technical terms but as a failure of personhood, the failure to be human, there is the possibility for motivation to arise for a more fully human course of action. This seems to me to be or to represent a chance that we can learn to more realistically protect life. Thinkability can lead to learning.

I’ve tried to think about these things ever since being a little annoyed by the term “Unthinkable” when I first heard it at the age of ten. I saw the clear moral imperative then, and it seemed to me that everyone else I knew did, too. I was briefly paid, in my thirties, (a tiny amount), to produce a newsletter called Radiation Events Monitor, (for a group called the Center for Atomic Radiation Studies, led by Dr. Donnell Boardman). I worked pro-bono with another lawyer, (Dan Burnstein), to help widows of “atomic veterans” seek compensation for their husband’s deaths from the Veterans Administration.[v] I went to conferences and met people touched by the tragedies of nuclear uses. The issues are complex, but some things become very clear when you turn your attention to them: many poisonings were truly unnecessary and the attitude that created and accepted them must be seen as heartless, mindless, or both. I don’t know enough to say anyone in particular is a principal villain here. I don’t even see this as caused by villainy at all, but rather by an absence, a lack of morality in the system, a hole, a wound, a cutting distance from the source forces of living intelligence.

Many take up the issue of the bombing of Hiroshima. There are arguments in favor of it. You may not like them, you may not want to like them, but they exist, and it is hard to imagine what it would have been like to be Harry Truman. But consider the argument for the bombing of Nagasaki.

The United States can and ought to show that it has the courage to look at itself and recognize the wrongfulness here even if we do not understand the reasons for it. Failure to acknowledge this original sin displays an inability to self-reflect which can feel like sociopathic behavior to others in the community of nations. It is a key turning point that we must understand. It seems to reflect the logic of momentum, the logic of overwhelming force. However we grasp at it we see there is something human missing at the very beginning. It is still missing.[vi]

Thinking that nuclear weapons could be a tool of diplomacy – that threatening their use would cause other countries to pay attention to our priorities – demonstrated a lack of historical understanding. Among the figures who launched “atomic diplomacy” was Truman’s Secretary of State James Byrne. The Atomic Heritage Museum puts it this way: he thought the bomb “might put us in a position to dictate our own terms at the end of the war.”[vii] By the age-old logic of military thinking, this seems clear, that the bomb is power, and what you want is to be dictating your own terms.

But history shows that people often get their back up when dictated to. Threatening to kill them can increase their resistance. The bombing of England stiffened resolve against Hitler, as Putin’s attack on the Ukraine has created a national movement to fight back, as our efforts in VietNam inspired the VietCong, to cite just a few examples. The idea that threatening to nuke a people will make them compliant is crude, childish, incorrect. Our nuclear threat today gives credence to the leader of the cruel North Korean state, and to the Supreme Leader of Iran, not to mention China. We can do better by thinking about nations the way we think about people, deserving of respect and willing to fight for their dignity. The nuclear option does not fit the real model of interpersonal relationships. It blows it up by its very existence.

Nuclear war is a personal issue for every citizen of the world because all life can be poisoned and billions killed. If we care about the safety of anything we have a responsibility to do what we can about this. It is a very frightening thing to think about, yes, but not unthinkable. If we can sit with the issue the chances of what we do regard as unthinkable happening will be reduced. It is primarily a socio-psychological matter, not one that the military can solve. As the back cover of Joel Kovel’s 1984 Against the State of Nuclear Terror puts it:

There are, says Kovel, two kinds of nuclear states. There is the nuclear state apparatus whose ruling principle is domination through science; and there is the nuclear "state of being" which includes the psychology of living under the nuclear gun. The nuclear crisis is not a matter (of) technically adjusting the nature and number of warheads, but the agony and paranoia of an entire civilization.”

It is not fun to think about what happened to people in Hiroshima, or how history will regard our creation and use of the threat, or the potential long-term world poisoning by fallout, nuclear winter, the generation of horrific wastes, the cancers caused. It seems easier not to select it as something to spend time on, and to leave it to others to think about. But that’s part of the story about why we remain in this hellish mess.

This movie will bring needed attention to the personal tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, a man who was humiliated after giving unstinting service to this country, considered a “crybaby” by Truman and smeared as possibly disloyal and/or untrustworthy. But his tragedy is a personal window into a much larger story about an impersonal force: the response to terror with the irrational concept that a greater terror will bring about safety. This logic created the arms race that now holds a knife to the throat of life on Earth. The challenge now is to use this moment to achieve some clarity about how we can move to reduce the threat of nuclear armaments.

If we get over the reluctance to think about it, we can actually see what does and does not make sense. The system of Mutual Assured Destruction and Nixon’s Madman Theory (if the other side believes you are crazy enough to push the button, they will give in) can no longer be regarded as sensible when we see how Putin is using it to prevent the US from arming Ukraine with the tools for a more responsive offense. The failure to disarm the nuclear system works to the advantage of the Madman, not us, or anyone. Nixon was wrong to use the theory.

Consider the binary deterrence system we are locked into with Russia. It makes little sense when other countries have gained nuclear weapons. History also shows the system can destroy the world by mistake. Recognizing the absurdity of inadvertently ending civilization should bring us up short and motivate rethinking.

Albert Einstein gave this matter a lot of thought and repeatedly said we needed supranational control. (We do have an international atomic energy body but it doesn’t control what’s going on). I am hoping that this movie will prompt more people to look back at what that smart man said, as, for example, in The Atlantic, in “Atomic War or Peace”, November, 1947:

…in blaming the Russians the Americans should not ignore the fact that they themselves have not voluntarily renounced the use of the bomb as an ordinary weapon in the time before the achievement of supranational control, or if supranational control is not achieved. Thus they have fed the fear of other countries that they consider the bomb a legitimate part of their arsenal so long as other countries decline to accept their terms for supranational control.

Americans may be convinced of their determination not to launch an aggressive or preventive war. So they may believe it is superfluous to announce publicly that they will not a second time be the first to use the atomic bomb. But this country has been solemnly invited to renounce the use of the bomb—that is, to outlaw it—and has declined to do so unless its terms for supranational control are accepted.

Thinking about nuclear issues can reduce the distress we feel, because thinking can lead to solutions, whereas ignoring the issue most certainly does not. If the movie leads to more people informing themselves, perhaps we can move from the primitive cultural reception of the nuclear age that named a sexy bathing suit after the island where the first demonstration blast was held, and gave us comic book heroes who gained superpowers by being irradiated.

Einstein drew attention, as he would do, to the fundamental laws in operation. His theory here of moral gravity seems proven by history:

It should not be forgotten that the atomic bomb was made in this country as a preventive measure; it was to head off its use by the Germans, if they discovered it…But now, without any provocation, and without the justification of reprisal or retaliation, a refusal to outlaw the use of the bomb save in reprisal is making a political purpose of its possession; this is hardly pardonable…

To keep a stockpile of atomic bombs without promising not to initiate its use is exploiting the possession of bombs for political ends. It may be that the United States hopes in this way to frighten the Soviet Union into accepting supranational control of atomic energy. But the creation of fear only heightens antagonism and increases the danger of war.

In 2020 Greg Mitchell, former editor of Nuclear Times, wrote in Newsweek:

Seventy-five years have now passed since the United States initiated a policy known as "first use" with its atomic attack on Hiroshima. Three days later, on August 9, 1945, it was affirmed with a second detonation over the city of Nagasaki. No nuclear attacks have followed since, although many Americans are probably unaware that this first-strike policy very much remains in effect.[viii]

No matter what we say about our first strike policy a military planner in another country would have to assume we might have one, and even if we were clear that we would not do that, the system of the second or only defensive strike still leads to a horrifying arsenal too easily triggered. A 2019 piece in Rethink Progress by Luisa Rodriguez reviews the current state of this expensive and dangerous standoff.

The degree to which a nuclear war between the US and Russia could escalate depends on how many of their nuclear weapons would survive a first strike.

Therefore, they maintain a secure second strike to maintain deterrence. She finds:

…between ~990 and ~1,500 of the US’s deployed nuclear warheads and between ~450 and~1,240 of Russia’s deployed nuclear warheads would survive a first strike. However, improvements in technology could substantially threaten the survivability of deployment systems that have been considered ‘inherently survivable’ for decades.[ix]

The whole system is only vaporously comprehensible and is inherently extremely unstable. Clearly, we must at least rapidly return to Oppenheimer’s sense of an appropriately sized defensive stockpile, and concentrate on bringing everyone together to create Einstein’s supranational body that can control these weapons. Clarity about what our goals should be, about the kind of country we want to be, that makes clear we are a people who want to live and want others to live, is thinkable if we try. The nuclear threat must be repudiated as a tool of foreign policy. Let us say, as people do love to say on both sides of our politics, that we are the strongest country in the world. But let us not say that we are the best until we have used our strength to bring everyone together to disarm the nuclear option for all the world’s sake.

Those who recommend this course of action will be marked for hostility on the theory that lowering your shield allows an enemy to slash you with their sword. But threatening to use nuclear weapons has not increased our power. We have preserved our power only because we have not used them in anger after World War II. But we have lost the opportunity to rally the world behind us because we used them coercively, as a threat. (Though the issue is a bit confusing in that nuclear bombs are only valuable if not used, that does not make the matter unthinkable, only ironic). When former atomic scientist Joseph Rotblat accepted the 1995 Nobel Peace Prize that he shared with the Pugwash movement for nuclear disarmament, he noted that

There is no direct evidence that nuclear weapons prevented a world war. Conversely, it is known that they nearly caused one.[x]

Out of the recognition that something doesn’t make sense can come a more sensible way of seeing. In the matter of nuclear issues, many things get in the way of seeing what needs to be seen, but we become better people for being able to see things as they are. It is painful to think about what happened to the people in Japan - to read, for example, Keiji Nakazawa’s graphic novels, based on his own life experiences as a child of Hiroshima, in the series Barefoot Gen. We don’t flock to the theaters to see Akira Kurosawa’s 1955 I Live in Fear, about a father desperate to get his family out of Japan before the Americans would bomb it again. Why should an American read these extraordinarily sad stories and watch that movie? Because they are the opposite of impersonal. The human element brings clarity about what is needed.

Reading about nuclear strategy can be distressing – all those bombs and bomb-making factories that generate horrendous amounts of pollution and create horribly poisonous materials that will last thousands of years and cannot be safely disposed of.

We don’t seem to like to think about the Navajo uranium miners not provided with respiratory protection, the servicemen marched to ground zero in test blasts that only served to show you could injure hundreds of thousands of loyal Americans, the Japanese boat The Lucky Dragon, (Daigo Fukuryū Maru), doused with intense fallout from our hydrogen bomb tests, or how those fearsome events made the Marshall Islands so radioactive people have lost their homes, and nuclear waste remains piled up waiting for the rising sea to disperse it.

But we are able to think about these issues and to see how they all come together into one conclusion: We must use our power to create a safer world, while we can. We should never have used the nuclear genie to wish for dominance. Recognition of the harm this has caused is the first step. Now we must ask the genies of the other lamps of power for the granting of our wishes for peaceful relations, just and beautiful cultures, the building of trust and friendship, the sharing of the fate of life on this green earth.

Rotblat used the Nobel Prize award to remind us all of the manifesto Einstein produced in 1955 with Bertrand Russell and others:

We need to convey the message that safeguarding our common property, humankind, will require developing in each of us a new loyalty: a loyalty to mankind. It calls for the nurturing of a feeling of belonging to the human race. We have to become world citizens…All nations of the world have become close neighbors…In many ways we are becoming like one family…In advocating the new loyalty to mankind I am not suggesting that we give up national loyalties. Each of us has loyalties to several groups – from the smallest, the family, to the largest, at present, the nation. Many of these groups provide protection for their members. With the global threats resulting from science and technology, the whole of humankind now needs protection. We have to extend our loyalty to the whole of the human race.

What we are advocating in Pugwash, a war-free world, will be seen by many as a Utopian dream. It is not Utopian. There already exist in the world large regions, for example, the European Union, within which war is inconceivable. What is needed is to extend these to cover the world’s major powers.

In any case, we have no choice. The alternative is unacceptable. Let me quote the last passage of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto:

We appeal, as human beings, to human beings: Remember your humanity and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open for a new paradise; if you cannot, there lies before you the risk of universal death.

The movie Oppenheimer tells a personal story about a key figure. But we are all key figures in this story. When medical officer David Bradley wrote in 1948 about his experience trying to respond to the radioactive mess produced by the second blast at Bikini Atoll (an underwater bomb exposed many naval personnel to serious wet radioactivity), he titled his book No Place to Hide. We are all personally affected by the failure to grapple with and remove the nuclear threat from our lives. When enough stop trying to hide from it and begin to engage, when enough see how thinkable it really is, we might get ourselves off this road that only leads to Hell on Earth. No good reason impels us to travel this way, and brighter directions demand our attention. Before us now is the act of 92 nations signing and 68 active parties in the 2017 United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons,[xi] nations that (or, perhaps better, who) among other things are

Deeply concerned about the catastrophic humanitarian consequences that would result from any use of nuclear weapons, and recognizing the consequent need to completely eliminate such weapons, which remains the only way to guarantee that nuclear weapons are never used again under any circumstances,

And are among other things

Determined to act with a view to achieving effective progress towards general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.

The future is in view and we can welcome and speed its arrival with the simple principles of friendly relationship applied to joint control that is “strict and effective”. Why not add the United States to the list of participants at https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVI-9&chapter=26&clang=_en? We might gain the strategic advantage of people not being afraid of us.

[i] See more at https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/16/science/j-robert-oppenheimer-energy-department.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/12/us/transcripts-kept-secret-for-60-years-bolster-defense-of-oppenheimers-loyalty.html

[ii] See, for example, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/coldwar/interviews/episode-8/york2.html or

“The Debate Over the Hydrogen Bomb”, Scientific American, Oct. 1, 1975, by Herbert York.

[iii] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-24280831

[iv] See Martin Sherwin’s 2020 Gambling with Armageddon.

[v] One of the husbands flew a plane that followed the radioactive cloud after bomb tests, and the pilot did not seem to have been given protective breathing equipment nor could we see that filters were used. We won one case but then it was overturned by HQ. When I later helped a former AF vet whose job involved long periods of time standing next to bombs (to reduce weight they have minimal shielding) I didn't mention his radiation exposure but submitted a claim based on his exposure to benzene. I had come to believe that the VA would not grant recognition of radiation injury because it would open the gates to a flood of claims from hundreds of thousands. We won full compensation.

[vi] The idea that momentum made the decision may be most appropriate, but that does not exclude factors like hubris or the doctrine of overwhelming force. For a great example of that at the very beginning of the colonial age see the story of how Magellan was killed, as told by William Manchester in his 1992 A World Lit Only By Fire. He seemed to think his display of new powers would frighten the enemy and that his righteousness would protect him.

[vii] https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/profile/james-f-byrnes/

[viii] https://www.newsweek.com/us-must-end-nuclear-first-strike-policy-opinion-1527038

[ix] https://rethinkpriorities.org/publications/would-us-and-russian-nuclear-forces-survive-a-first-strike

[x] https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1995/rotblat/lecture/

[xi] https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/2017/07/20170707%2003-42%20PM/Ch_XXVI_9.pdf

RSS Feed

RSS Feed